What is a Vitamin?

- David S. Klein, MD FACA FACPM

- Jan 13

- 4 min read

A physician’s guide for patients—clear, evidence-based, and practical.

Most people take vitamins, yet surprisingly few understand what a vitamin actually is. The term is often used loosely to describe anything sold in a supplement aisle, but in medicine and biology, vitamins have a precise definition. Understanding that definition—and where important exceptions exist—helps patients make better decisions about nutrition, supplementation, and long-term health.

A vitamin is an organic compound required in small amounts for normal metabolism, cellular function, growth, and repair—and one that the human body cannot synthesize in adequate quantities on its own.

This definition matters.

If the body can make enough of a substance, it is not a vitamin.

If the substance is inorganic (such as calcium or iron), it is a mineral, not a vitamin.

Vitamins occupy a narrow but essential biological category.

The two major vitamin families

Vitamins are traditionally classified by how they are absorbed, transported, and stored.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Fat-soluble vitamins dissolve in dietary fat, are absorbed through the intestinal lymphatic system, and can be stored in body tissues, particularly the liver and adipose tissue.

They include:

Vitamin A

Vitamin D

Vitamin E

Vitamin K

Because they are stored, deficiencies usually develop slowly—but excessive intake can accumulate and cause toxicity.

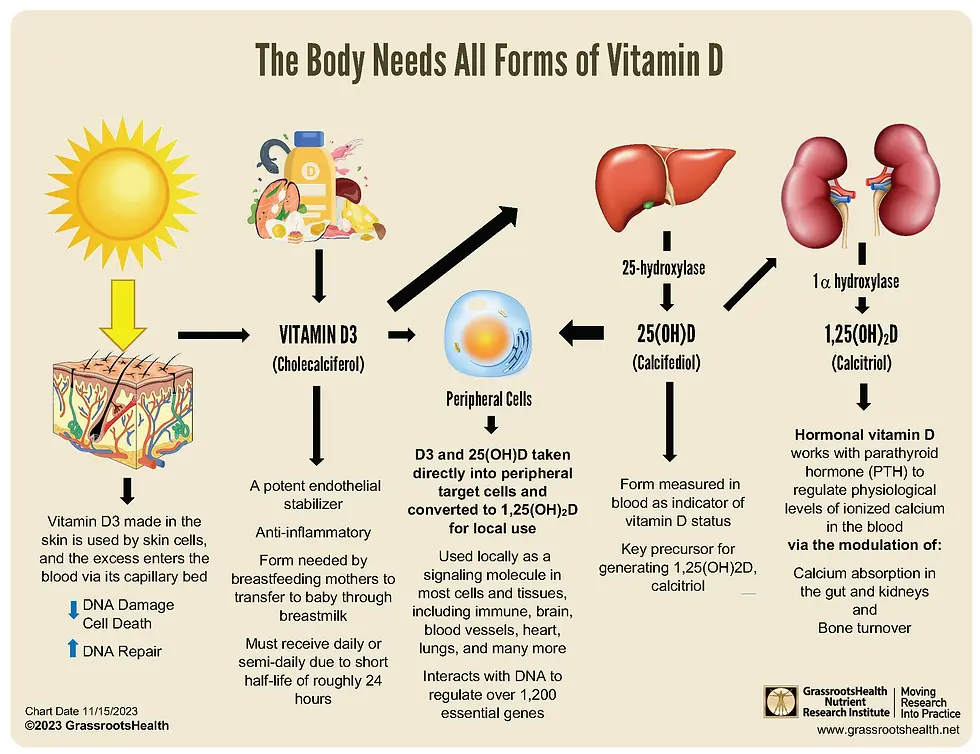

Although vitamin D is traditionally grouped with fat-soluble vitamins, it functions biologically as a hormone, not a true vitamin.

Unlike other vitamins, vitamin D can be synthesized by the human body when ultraviolet B (UVB) sunlight interacts with cholesterol in the skin. It is then activated in the liver and kidneys to form calcitriol, a steroid (secosteroid) hormone that binds to nuclear receptors and directly regulates gene expression.

Vitamin D receptors are found throughout the body, including bone, muscle, immune cells, the cardiovascular system, and the brain. This explains why vitamin D affects bone health, immune regulation, inflammation, insulin sensitivity, neuromuscular function, and more.

It remains labeled a “vitamin” largely for historical reasons, because deficiency was first recognized through dietary disease (rickets). Clinically, it is more accurate to think of vitamin D as a hormone with vitamin-like deficiency states, which is why blood testing and individualized dosing are often appropriate.

Water-soluble vitamins

Water-soluble vitamins dissolve in water, circulate freely in the bloodstream, and excess amounts are usually excreted in urine.

They include:

Vitamin C

B-complex vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12)

Because they are not extensively stored, deficiencies can develop more quickly, particularly with poor intake, malabsorption, medication effects, or increased metabolic demand.

Vitamins vs hormones: a simple comparison

Many patients are surprised to learn that vitamin D behaves more like a hormone than a vitamin. The distinction is helpful.

In simple terms:

Vitamins must come primarily from the diet and act mainly as enzyme cofactors.

Hormones are produced in the body, circulate as signaling molecules, and regulate gene expression and organ function.

Vitamin D sits at the intersection of these categories.

What vitamins actually do

Vitamins do not provide energy or calories. Instead, they enable the chemical reactions that allow cells to function.

They commonly act as:

Enzyme cofactors

Regulators of cellular metabolism

Antioxidants

Facilitators of neurotransmitter and hormone synthesis

Without adequate vitamin availability, metabolic pathways slow or malfunction—even when calories are plentiful.

Why deficiencies still occur

Vitamin deficiency is not confined to poverty or famine. Subclinical deficiency is common, especially in older adults.

Common contributors include:

Highly processed diets

Reduced appetite or restrictive eating

Gastrointestinal disorders or surgery

Certain medications (e.g., metformin, proton-pump inhibitors)

Reduced sun exposure

Increased needs with aging, illness, or stress

Symptoms are often subtle at first—fatigue, neuropathy, cognitive slowing, immune vulnerability, or bone loss.

Food first—usually

Whole foods remain the preferred source of vitamins because they provide supportive nutrients that enhance absorption and utilization.

Examples include:

Leafy greens → folate, vitamin K

Fatty fish → vitamin D, vitamin A

Citrus and vegetables → vitamin C

Eggs and meats → B12, biotin

However, food alone does not always meet needs.

When supplementation is appropriate

Supplementation is often reasonable when:

A deficiency is documented

Absorption is impaired

Dietary intake is consistently inadequate

Requirements increase with age or illness

Evidence supports benefit in deficient individuals

The goal is targeted supplementation, not indiscriminate use.

More is not better

Excess intake—particularly of fat-soluble vitamins—can cause harm. The objective is physiologic adequacy, not maximal dosing.

Bottom line

A vitamin is not a marketing term or wellness trend. It is a biologically essential compound required for normal human physiology. Vitamin D stands apart as a hormone that behaves like a vitamin only in deficiency.

Understanding these distinctions empowers patients to approach nutrition and supplementation with clarity, realism, and safety—ideally guided by medical evidence and individualized care.

References

Combs GF. The Vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. Elsevier; 2012.

Ames BN. Low micronutrient intake may accelerate aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(47):17589-17594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17101960/

Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266-281. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17634462/

Christakos S, et al. Vitamin D metabolism, molecular mechanism of action, and pleiotropic effects. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(1):365-408. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26681795/

O’Leary F, Samman S. Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients. 2010;2(3):299-316. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22254022/

Troesch B, et al. Increased micronutrient needs with aging. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:231-245. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22888231/

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamins and Minerals Fact Sheets. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Schleicher RL, et al. Trends in vitamin status in the U.S. population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(1):274-284. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26702154/

EFSA Panel. Tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins. EFSA J. 2018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamins. National Academies Press; 2011.

1917 Boothe Circle, Suite 171

Longwood, Florida 32750

Tel: 407-679-3337

Fax: 407-678-7246

.webp)