top of page

Search

Baastrup’s Disease: The Overlooked Cause of Midline Low Back Pain

Baastrup’s disease—also called kissing spine syndrome—is a degenerative condition in which adjacent lumbar spinous processes contact one another, producing focal midline back pain. Often mistaken for disc disease, it typically worsens with extension and improves with flexion. Accurate diagnosis allows targeted treatment and may prevent unnecessary procedures.

David Stephen Klein, MD FACA FACPM

2 days ago4 min read

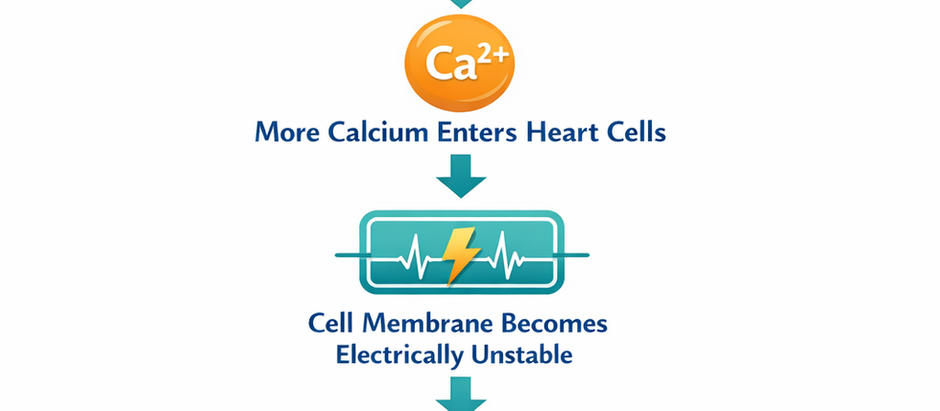

Magnesium Deficiency: The Overlooked Driver of Arrhythmia, Insulin Resistance, and Anxiety

Magnesium deficiency is common and often missed. Low magnesium contributes to arrhythmias, insulin resistance, anxiety, and metabolic dysfunction—frequently despite “normal” serum labs. Learn how magnesium affects cardiac stability, insulin signaling, and neuroexcitation, and why correcting intracellular deficiency may improve cardiometabolic and neurologic health.

David Stephen Klein, MD FACA FACPM

4 days ago4 min read

Measles Resurgence in Florida: Understanding the Risks, Prevention, and Cost–Benefit of Vaccination

Recent measles cases in Florida underscore how quickly this highly contagious virus can spread when vaccination rates decline. Measles carries significant risks including pneumonia and encephalitis, and outbreaks impose substantial public health costs. The MMR vaccine remains a highly effective and economically sound preventive strategy that protects individuals and vulnerable communities.

David Stephen Klein, MD FACA FACPM

5 days ago5 min read

bottom of page